The Spanish flu was a global pandemic that occurred in 1918-1919, caused by an H1N1 influenza virus. It spread quickly and infected about a third of the world’s population, leading to millions of deaths. The virus was especially deadly because it affected healthy young adults, not just the elderly or sick.

Except, well, that isn’t true.

The official story is bunk.

The flu was a man-made disaster. It was not the germs that killed, but the vaccines and suppressive drugs administered by the authorities.

—Eleanor McBean, author of The Poisoned Needle

So, if the official story is bunk, what is the truth?

There was no virus

Michael Bryant, in his outstandingly researched article, Exploding the Spanish Flu Myth, notes that the Spanish flu wasn’t caused by a virus, but by the harsh environmental conditions of World War I.

In other words, there was no evidence of a deadly pathogen spreading between people.

What happened, as Michael explains, was a collection of war-related consequences.

I mean, isn’t it a total coincidence that WW1 and the Spanish flu ended around the same time?

Factors like chemical warfare, overcrowded and unsanitary living spaces, and mass vaccinations created the perfect storm for illness.

The primary vectors to ‘the Spanish flu’ were:

chemical warfare toxins affecting soldiers and civilians

overcrowded and unhygienic wartime conditions

experimental vaccines and medical treatments

The vaccinations given to American soldiers during the war sparked a wave of illness like we’ve never seen before, one that conveniently distracted from the political and economic upheavals of the time.

—Frederick T Gates (Rockefeller Foundation)

It was always the war

Young, healthy men were the hardest hit, not because of a virus, but due to the brutal conditions they faced.

Why would healthy men ranging between age 20 and 40, mostly soldiers and war staff, be most affected?

Because it wasn’t their immune systems failing them; it was the toxic stress of war.

People quickly forget the brutal introduction of trench warfare, chemical weapons, and modern tech like machine guns and tanks, leading to massive casualties and horrific conditions for soldiers and civilians.

Additionally and somewhat crucially, as Michael highlights, there’s no pathogenic evidence in historical records suggesting that a virus caused the Spanish flu.

The Rosenau Experiment

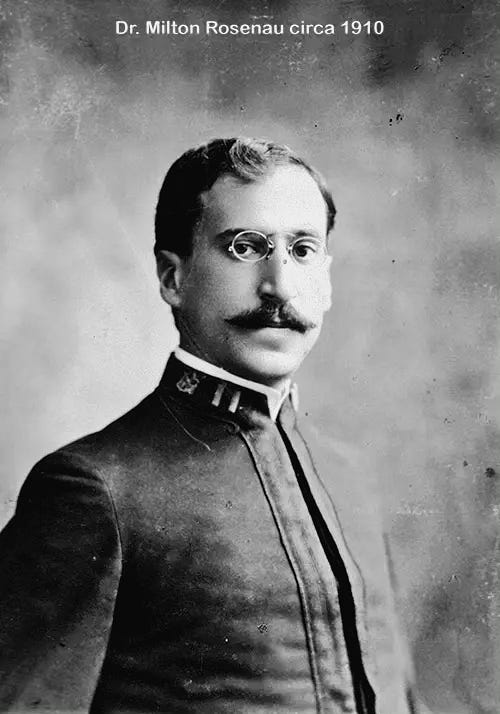

The Rosenau Experiment, headed by Harvard’s Milton Rosenau and funded by the US Public Health Service, aimed to show that the Spanish flu was contagious.

It failed.

Not one of the 62 healthy volunteers became ill. More volunteers were used later, and they didn’t get sick either.

Basically, they inhaled the breath of infected patients, had secretions from the noses and throats of the sick rubbed into their eyes, noses, and mouths, and even received blood injections from sick patients.

Nothing happened.

Nobody fell ill.

Rosenau concluded that he had no idea what was going on.

We entered the outbreak with a notion that we knew the cause of the disease, and were quite sure we knew how it was transmitted… Perhaps… we are not quite sure what we know about the disease.

—Milton Rosenau, 1919

Some of the talking points of our conversation included:

Understanding the Spanish flu and its misconceptions

The role of World War I and its impact on health

Chemical warfare and vaccination campaigns during the war

The Rosenau experiment and disease transmission

Demographics of Spanish flu victims and causes of death

Bacterial infections, masks, and the cover-up of real causes

Is it unreasonable to suggest that the primary cause of deaths attributable to the Spanish Flu was everything related to WW1

—Michael Bryant